PTSD affects brain circuitry

How your brain functions and how the various parts are supposed to work.

By:

Mind - Mental Health

-

3/2/2017

-

Page Image 1

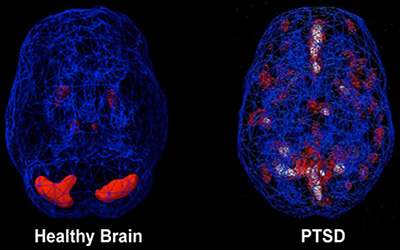

Not everybody with PTSD has exactly the same symptoms or the same brain changes, but there are observable patterns that can be understood and treated.

-

Page Image 2

When your hippocampus doesn't work right, you can't recall important memories when you need them, or fearful ones turn up at the wrong times, confusing your sense of "right now."

-

Slider Image

Page Content

If you're experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder, it might help to have an idea of how your brain functions and how the various parts are supposed to work. Sometimes just understanding what's going on in your brain facilitates the process of recovery and can boost understanding of the treatments used to help rewire your brain to get back on track.

Post-traumatic stress is a normal response to traumatic events. PTSD is a more serious condition that impacts brain function and often results from traumas experienced during combat, disasters, or violence.

Your brain is equipped with an alarm system that normally helps ensure your survival. With PTSD, this system becomes overly sensitive and gets triggered too easily. In turn, the parts of your brain responsible for thinking and memory stop functioning properly. When this happens, you have difficulty separating safe events happening now from dangerous events that happened in the past.

Background

Over the past 40 years, scientific methods of "neuroimaging" have enabled scientists to see that PTSD causes distinct biological changes in the brain. Not everybody with PTSD has exactly the same symptoms or the same brain changes, but there are observable patterns that can be understood and treated.

The Brain's Alarm System

The diagram shows a cross section of the brain, and illustrates the parts discussed here.

The amygdala of your brain triggers your natural alarm system. When you experience a disturbing event, it sends a signal that causes a fear response. An extreme fear response makes sense when your alarm bells buzz at the right time and for the right reason: t o keep you safe.

Those with PTSD tend to have an overactive response, so something as harmless as a car backfiring could instantly trigger panic. The amygdala is a primitive animalistic part of the brain, wired to ensure survival; when it's overactive, it's hard to think rationally.

Your Brake System

Your brain's prefrontal cortex, the front-most part of the neocortex, helps you think through decisions, observe how you're thinking, and put on the brakes when you realize something you first feared is actually not a threat after all. The prefrontal cortex helps to regulate emotional responses triggered by the amygdala. In operators and enablers with PTSD, the prefrontal cortex doesn't always manage to do its job when it's needed.

A Bad Combination

An overactive amygdala combined with an underactive prefrontal cortex creates a perfect storm. It's like stomping on the accelerator of your car, even when you don't need to, only to discover the brakes don't work. This might help you understand why someone with PTSD might: feel anxious around anything even slightly related to the original trauma that led to the PTSD; or have strong physical reactions to situations that shouldn't provoke a fear reaction; and avoid situations that might trigger those intense emotions and reactions.

System Recall Errors

Other common PTSD experiences—such as unwanted feelings that pop up out of nowhere or always being on the lookout for threats that could lead to more trauma—seem to be related to the hippocampus, or memory center of your brain. When your hippocampus doesn't work right, you can't recall important memories when you need them, or fearful ones turn up at the wrong times, confusing your sense of "right now". You can't match up the fact that you're safe (or not) with the right memories.

Overcoming PTSD

Treatment techniques for PTSD include cognitive restructuring, stress inoculation training, and exposure therapy. With cognitive restructuring, you learn new ways to think about things—reframing your thoughts—to match current conditions. It also helps you become aware of cognitive errors in your thinking and learn strategies to correct them. It helps you experience different feelings and different reactions. For instance, you might replace "I can't handle this anxiety," with "I don't like these feelings, but I can handle them, and they'll pass."

Stress inoculation teaches you to anticipate stressful events and know that you can handle them with minimal discomfort. You learn to habitually pair things that trigger fear with relaxation techniques and coping strategies, which enables you to manage your anxiety when stress comes along.

Exposure therapy exposes you to alarming stimuli in a safe way, pushing your body and mind into recognizing when you're safe. It's like watching a scary movie repeatedly until it doesn't scare you any more. It helps your alarm system avoid misfiring. It also helps you access relevant memories so you know if you're safe. And it helps you access your mental brakes so that, when your alarm does ring, you can apply the brakes if you need to.

Debrief

Your amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus all contribute to the emotions and actions associated with fear, clear thinking, decision-making, and memory. Understanding these parts of your brain and how they work also might help you understand why some therapies can help you work through PTSD.

For a visual guide to these and other parts of your brain, and more information about them, explore the Center of Excellence for Medical Multimedia's Interactive Brain. Click on "Inside View" to locate the areas described above, and hover your cursor over the red dots. To view the hippocampus, find the 'limbic system' dot near the lower left, click on it, and read the description.

PTSD affects brain circuitry.aspx

Related Articles